Editor’s note: This post was submitted by Tucson Velo reader, Kevin Foote.

Climbing Mt. Lemmon was nothing compared to the effort that will be required to repair this lemon, I think to myself.

Hanging from the repair stand in my garage is a dirt-caked, Murray All-Terrain Mountain Bike. It’s the kind of mass-produced, inexpensive bike sold at big box retailers nationwide; the sort of bike that your LBS (local bike shop) refers to as a POS.

Accordingly, it’s unlikely to be stolen. Which brings me to why I am in my garage, tools at the ready, gearing myself up for a wrenching start.

Twelve weeks ago my wife left her bike on the University of Arizona campus on a Friday night. We realized the oversight overnight, and by Saturday morning it was gone.

It had been hitched to a rack with a cable lock which stood little chance against a decent pair of bolt cutters. Every bicycle that had survived the night was fastened with a U-lock.

My first lessons in theft prevention since moving to Tucson: Bring your bike home with you at the end of the day and use a U-lock.

At the recent GABA Bike Swap I felt like the tragic-hero of the sublime Italian film Bicycle Thieves, searching despondently for an unscrupulous individual pedaling hot wares.

I emailed every bicycle shop in town asking mechanics to be on the lookout for a stolen KHS Flite 250.

Only BICAS (Bicycle Inter-Community Art and Salvage) responded. To avoid selling stolen merchandise, they simply don’t purchase bicycles.

Knowing nothing about BICAS but impressed by their reasonable policy, I set out to learn more.

BICAS is a non-profit bike repair and recycling collective at the corner of 6th Street and 9th Avenue. The collective sells used bicycles and parts and rents out tools for day-use in their cavernous confines.

The organization also hosts courses in bicycle building and repair, including a comprehensive eight-week Build-A-Bike course whose participants pay $80 for 24 hours of instruction.

In need of a bicycle, or the skills required to restore one to rideable condition, I signed up.

This brings me to today, seven weeks into the course. Eyeing the Murray in my garage, I recall one backhanded compliment on a bicycle review website: it will one day be recycled into a washing machine.

Disheartened, I wipe the grime from its headset and make out the words: Lawrenceburg, Tennessee 1990. “What do you know, Walmart used to sell things made in the U.S.?”, I say to myself as I fit a fifteen millimeter wrench around the left pedal bolt and yank it counterclockwise. The bolt doesn’t budge.

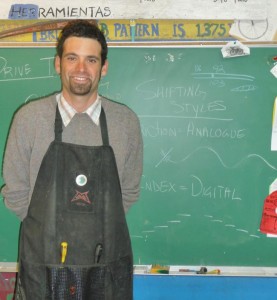

Our teacher, Ignacio Rivera de Rosales, peppers his mechanical wisdom with historical asides about bicycle culture and the evolution of components. Throughout the underground repository of discarded bicycles and parts, which I’ve been told could double as a sweat lodge during the summer months, most tools and instructions are labeled in English and Spanish.

Two apprentice mechanics assist Ignacio. He playfully refers to his assistant, Luke, as “Skywalker,” and one undergraduate physics student as “The Astrophysicist.”

The male and female students range in age from pre-teen to post-retirement, the latter proud to have lost close to forty pounds since taking up cycling this past summer.

On the first day of class, participants had split up into pairs. Each duo worked on a bicycle with tools provided by BICAS.

At the conclusion of the course, students have the option of purchasing their bicycle for a nominal fee. The drama of determining which participant of each team has the first right of purchase has yet to unfold.

As I am paired with a taller student and have been charged with repairing a 51-cm women’s-style pink Centurion, I feel good about my wife’s chances of procuring a refurbished bicycle in time for the holidays.

As I apply some lubricant to the pedals of the Murray, I recall the first class. We had disassembled our bicycles and not yet begun overhauling the headset, crankset, hubs, spokes, brakes and drivetrain.

“I want you to think of bicycle repair as the learning of a language rather than the memorization of an algorithm,” Ignacio said, flashing a smile at The Astrophysicist.

The rules of the English language are rife with exceptions, and so are the rules for repairing a bicycle. We were working on a variety of bikes and components from different countries and eras, so a slogan like “tighty-righty, lefty-loosey,” would not always guide our actions.

Remembering Ignacio’s words, I grip the drive-side pedal of the Murray as I apply clockwise pressure to the left pedal. With a little force, the bolt begins to loosen.

Setting out to restore the Murray, my plan was to follow the same step by step procedure that I was taught in class.

Having removed the pedals and wheelset and cleaned the frame thoroughly, I turn my attention to the headset. Clamping an adjustable end wrench around the top of the headset, I try to loosen its octagonal locknut, but each time the jaws of the wrench slip and further strip the edges.

“Surface area,” repeats Ignacio, opening the second class, “surface area is the correct answer.”

Anytime Ignacio asks us a question for which no one knows the answer, someone shouts, “surface area!” It has become a running joke, but contains an important lesson when it comes to choosing the right tool for a job. My two-sided adjustable wrench, unlike the five-sided headset wrench found at BICAS, offers insufficient surface area to grip and turn the eight-sided locknut.

Scanning my workbench for a different tool, I am struck by another similarity between bicycle repair and language aquisition: sometimes there is another tool or word within your reach that will suffice.

Other times, you need to borrow a tool from BICAS or consult a thesaurus. I will bring my Murray to BICAS and remove the headset there. But for now I’ll have to shift gears in order to keep the conversation going.

Turning to my front hub, I remove the ball bearings and judge their luster or — to use Ignacio’s amusing term — blingosity. Polishing the bearings with a rag and finding that they have sufficient bling left, I repack them in the hubs using fresh grease.

The ball bearings in the hubs are the points of contact (surface area) between a bicycle’s frame and wheels.

Overhauling the hubs is one of the most important and difficult procedures of bicycle maintenance; and one that I will not easily forget due to Ignacio’s likening of the ball bearing system to a chunky peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

If that doesn’t whet your appetite to take the course, then I’ll leave you with a few final thoughts.

Ignacio succeeds as a teacher, in part, because he challenges his students to grapple with problems and attempt their own repairs before seeking advice or assurance. This style of learning breeds temporary frustrations. For instance, while Ignacio could probably have identified the correct nut for a pinchbolt on our brakes within a matter of seconds, my partner and I were left to sort though a drawer of bolts on our own.

It was as though someone had poured me a bowl of Cheerios and asked me to identify the one with the smallest hole. But the pride I felt at spinning the crank arm on the pink Centurion — marveling at its smooth glide, and knowing that I had managed the repair myself, reinforces the value of Ignacio’s technique.

The course is coming to an end, and the Murray still hangs from my stand, several repairs closer to its test ride. I’m not sure how the department store special will hold up. Will its flimsy rims bend the first time I hop a curb? Will the chain ever shift smoothly from sprocket to sprocket? The Build-A-Bike course at BICAS encourages me to fix my purchase rather than purchase a quick fix.

And while the Murray was free, and still won’t look like much to a thief, I’ll be sure to use a U-lock when I stable my handiwork.

Editor’s note: Kevin says the BICAS class fills up quickly and he was only able to get in because of a cancellation. The next Build-a-Bike class starts Jan. 11, 2011. Sign up by calling BICAS at 520.628.7950.

If you are interested in contributing a story to Tucson Velo, please contact me.

Had a friends bike stolen at Uof A and through alot of calls and leg work found bike at Play it Agian Sports. Play it again has name of person that sold them bike but Uof A police have yet to respond. To get bike back they want the money they paid for bike from the owner. Wonder why they don’t check ownership before purchase. So if you are missing a bike check Play it Again Sports you might fine your bike there.

I took the Build-a-bike class about a year ago and I would recommend it. I learned a lot and Ignacio was great. If you are looking to expand your bike knowledge, take this class!

This is a well written article. I live over 1000 miles from Tucson and I am tempted to take one of his classes. Whether or not I ever get to Tucson, the article sold me on what to look for in a bike repair class. Ignatio seems ready to immerse anyone in how to make a bike work if that person really has the interest in getting immersed.